|

God became man.

The "earthy" reality of the Incarnation is probably one of the main

concepts the focusing on which separates Catholics (and Orthodox) from

most other Christians. Adherents to more Puritanical forms of

Christianity are scandalized by images; seeing a Corpus on a Crucifix

instead of an empty Cross, seeing churches adorned with statues and

other icons, etc. seem so -- "undivine" or "wordly" to these people;

but we Catholics know that Christ, by taking on flesh and becoming man,

redeemed us and gave to us the offer of a dignity which, without Him,

would be impossible. It is to always be remembered that we are not

souls trapped in flesh, but enfleshed souls who are called to use our

bodies and time on earth glorifying Him and, in consequence, becoming

divinized and sharing in His Divine Nature. Our time in this material

world isn't some kind of cruel joke.

All Truth, all Beauty, all Goodness point to Him, amen, and the

beautiful and good things of this world are a shadow of the world to

come. Our statues and other icons help us to see this as they also

inspire us to meditate on the specific divine realities they mean to

convey. When Christ incarnated at the Annunciation and was born of the

Virgin nine months later, He demonstrated one of the first Biblical

Truths: what God made is good, and flesh, while humbling for God to

take on, while weak, and while prone to corruption and sin after the

Fall, is not inherently evil. Christian understanding of the

consequences of this reality is evident from the beginning, as far back

as the Catacombs, and two-dimensional painted icons, statues, and

mosaics have always been used as aids to Christian worship.

Nonetheless, during the 8th c., two great waves of iconoclasm struck

Christianity in the East, the first led by Emperor Leo III who was

influenced by the success of iconoclastic Islam and a revival of the

Monophysite heresy which denied Christ's humanity. Pope Gregory II

denounced Leo and his iconoclastic movement, and the Seventh Ecumenical

Council at Nicaea (A.D. 787) firmly explained the difference between

idolatry and the veneration given to icons. Pope St. Gregory the Great

explained this difference and extolled images' catechetical value in a

letter he wrote to an iconoclast Bishop:

Not without

reason has antiquity allowed the stories of saints to be painted in

holy places. And we indeed entirely praise thee for not allowing them

to be adored, but we blame thee for breaking them. For it is one thing

to adore an image, it is quite another thing to learn from the

appearance of a picture what we must adore. What books are to those who

can read, that is a picture to the ignorant who look at it; in a

picture even the unlearned may see what example they should follow; in

a picture they who know no letters may vet read. Hence, for Barbarians

[those who don't speak Latin] especially a picture takes the place of a

book.

Icon painter,

Leontius the Hierapolian, wrote about the Christian use of images:

I sketch and

paint Christ and the sufferings of Christ in churches, in homes, in public squares and on icons,

on linen cloth, in closets, on clothes, and in every place I paint so

that men may see them plainly, may remember them and not forget them...

And as thou, when thou makest thy reverence to the Book of the Law,

bowest down not to the substance of skins and ink, but to the sayings

of God that are found therein, so I do reverence to the image of

Christ. Not to the substance of wood and paint -- that shall never

happen... But, by doing reverence to an inanimate image of Christ,

through Him I think to embrace Christ Himself and to do Him

reverence... We Christians, by bodily kissing an icon of Christ, or of

an apostle or martyr, are in spirit kissing Christ Himself or His

martyr.

Nonetheless, the

iconoclasts raged on in the East, and Christians there begged the Pope

to intervene, with St. Theodoret writing:

Whatever novelty

is brought into the Church by those who wander from the truth must

certainly be referred to Peter or to his successor... Save us, chief

pastor of the Church under heaven...Arrange that a decision be received

from old Rome as the custom has been handed down from the beginning by

the tradition of our fathers.

Eventually, with

the popular help of Empress Theodora in A.D. 843, the iconoclastic

nonsense was finally squelched, but not until after monasteries were

trashed, icons were smashed, monks were tortured and killed, and relics

and shrines destroyed.

When the same heresy arose in the West during the Protestant

rebellions, the same thing happened: churches and Altars and

altarpieces were destroyed, statues and 2-dimensional icons smashed,

stained glass crushed, chalices and other liturgical

vessels melted down, and monks, nuns,

and priests killed. These things were endured again at the consequent

rise of secularism, especially during the bloody French Revolution,

when a prostitute was "enthroned" at the Altar of Paris's Notre Dame

and renamed the "goddess of Liberty". Nowadays, the

outrages are committed mostly by Muslims and Communists all over the

world; by anti-Christian Jews in Israel; and in isolated but

increasingly common incidents caused by Satanists, rowdy teenagers, and

political activists venting their rage against the Church (there are

also still incidents perpetrated by anti-Catholic Protestants in South

America). In a broader sense, one can see the spirit of iconoclasm in

much of (often publicly-funded) modern "art" with its dung-speckled

Madonnas, Crucifixes submerged in

glasses of urine, etc. (It's fascinating and sad that public money

would never go to fund artistic depictions of Our Lady or the Crucifix

-- unless they were defiled in some way, at which point they become

"art" and matters of "free expression.")

2-D Icons

Though the word

"icon" (also "ikon" or "eikon") refers to religious images of any sort

-- 2-D, 3-D, made of any material, in this section, I will use the word

to refer specifically to two-dimensional representations which have

become highly stylized over time and which one typically associates

with the word "icon." Like all religious images, an icon has as its

purpose acting as a "window to Heaven," a portal through which one sees

greater Truths than can be revealed by word alone.

Christ is the first icon in that He revealed the Father ("He who has

seen Me, has seen the Father," John 14:8-9); we ourselves are creatures

made in the image of God and who are to put on Christ in order to

restore our likeness to Him. We are called to be iconic in that

we are to reveal the Father in our Christian witness, through the grace

of Christ and the Gifts of the Holy Ghost. And, of course, there is the

Holy Shroud which was made without human hands...

While the first Icon Maker is God -- Who begot the Son Who is God and

Who reveals

the Father, Who created us who are called to reveal Him, and Who

miraculously formed the Holy Shroud, St. Luke is said to have made the

first icon made by human hands: an icon called the Hodegetria -- a

prototype of the Eleousa icon (Our Lady of Tenderness) which is an

image of Our Lady holding her Son. Over time, icons came to be painted

according to very definite rules of design and system of symbols (see table below); the arrangement of elements, colors

used, the manner of showing light, etc. are all governed by theological

principles and ecclesiastical custom. Various schools and ages of icon

making arose, each with distinctive styles: the 6th c. Justinian

period; the 10th c. - 12th c. rise of Russian icon writing; and the

"Golden Age of Icons" in the 14th c. Throughout, the representations of

persons were and are meant to capture spiritual realities, not earthly

ones. They are not meant to be realistic portraits of their flesh, but

portraits of their enfleshed spirits, as it were, as seen through the

eyes of faith.

As you can see from where the great schools of icon writing arose,

two-dimensional highly stylized icons are a more important phenomenon

in the East than in the West, where statues, mosaics, illuminated

manuscripts, stained glass, etc., also had their place, and the means

of the veneration of images in the East and West also differ according

to custom:

East:

prostrations (inside of Lent), bows (outside of Lent), kisses to the

feet or hem of the one depicted, incense, processions,

and burning

candles before the image are used to show one's veneration for the

Divine Reality presented by the image

West:

kisses to the feet or hem of the one depicted, touching the image,

burning candles before the image, kneeling, incensing, processions,

adornment with flowers, and crownings (esp. of Marian icons) are more

the form. Prostrations are reserved for the Crucifix. (See more on posture and gesture here.)

Veneration is

also shown to some icons by decorating them with gems and/or a cover

(called an oklad) made of silver, gold or other metal.

Symbology in Icons

| Hands |

hands are often

shown giving a blessing: the last two fingers touching thumb (two

fingers raised) symbolizes the two natures of Christ; ring finger

touching thumb (three fingers raised) symbolizes the Trinity.

Hands are also shown with with the forefinger extended straight; the

middle finger curved slightly; the thumb and the ring finger crossed;

and the little finger curved slightly. This gesture forms the letters

"IC XC" (Greek letters for "Jesus Christ") -- the first finger making

the I, the curved middle finger forming the C, the crossed ring finger

and thumb forming the X, and the pinky finger forming the second C. |

| Eyes |

large to show

faith in God ("the eyes of faith") |

| Ears |

large to show we

must listen to God |

| Position |

usually, divine

and saintly figures face forward; others are in profile |

| Light |

Light source

shown as coming from within the Divine or divinized Person or persons |

| Color |

Gold: Divine

Light, Christ Himself

White: eternal Light, the Father

Green: Holy Spirit, regeneration

Blue: faith, humility

Red: youth, beauty, war, love

Purple: royalty, priesthood

Bright Yellow: Truth

Pale Yellow: pride, betrayal

Brown: death to the world

Black: evil, death |

| Time and Space |

earthly

perspective is lost and icons have a flatness to them that disappears

in Western Art after the painter Giotto discovered the rules of

painting using perspective. Time, too, is distorted to show sequential

events simultaneously. Both of these phenomena lend themselves to

aiding the viewer in realizing that he is not looking at temporal

realities, but spiritual realities |

| Evangelists |

wear tunics,

carry a book |

| Bishops |

wear vestments,

carry a book or scroll |

| Monks |

wear habits,

stand very erect |

Reading Icons

Let's take a

look at the icon of Our Lady of Perpetual Help (also called "Our Mother

of Perpetual Help" and "Virgin of the Passion") to get an idea of

how to read icons. But first, a little history, because the story of

this icon is so interesting.

No one is sure about the origins of the icon, but it came from Crete

and is a "Hodegetria" style icon (see below). A merchant there heard of

many miracles surrounding the icon and, wanting it for himself, stole

it and took it with him in his travels. He ended up in Rome, and on his

deathbed, told a local Roman about how he'd acquired the icon and asked

him to take it to a church where it could be enjoyed by many. The

Roman's wife, though, had other ideas and kept the icon in her bedroom.

Mary appeared to the Roman many times in visions, asking him to take

the icon to a church. When this didn't happen, Mary appeared to the

Roman's six-year old daughter and told her the icon should be taken to

St. Matthew Church. The Roman family obeyed, and there the icon

remained, venerated by many who came to contemplate its message, until

1798 when Napoleon's army invaded Rome and Napoleon (what else?)

ordered the destruction of churches. The icon disappeared.

Around 50 years later, a sacristan in a church in France told an altar

boy that the painting that had hung in their own church for almost a

half-century was very old and used to hang at St. Matthew's church in

Rome. It had been saved from destruction and secretly carried to their

parish church, and he wanted the boy to remember this so someone

would know the story.

More years pass, and the altar boy had become a Redemptorist in Rome.

His Order took over an estate that just happened to include the old St.

Matthew church, and while researching the history of the place, they

learned of the beautiful icon that had disappeared. The former altar

boy remembered what the sacristan had told him and relayed the story to

his Brothers. The Redemptorists appealed to Pope Pius IX, reminding him

that it was Mary's own wish that the icon be hung at St. Matthew's

church. The Pope intervened, restoring the icon to its now rightful

place, and telling the Redemptorists to make Our Mother of Perpetual

Help their mission, spreading knowledge of her and her icon throughout

the world. This they have done.

And now on to the icon itself:

Mary's gaze is aimed directly at you, as though she wants you to meet

her eyes and ponder. The Greek letters above -- MR QU -- tell us that she

is the Mother of God, and, against a background of gold (divine light),

she wears a dark blue robe (faith, humility) with a green lining (Holy

Ghost) and a red tunic (beauty).

Baby Jesus, identified by the letters "IC XC," doesn't look at His

mother or at us in this icon; instead, He is looking away, having seen

something that made Him afraid -- so afraid that He ran to His mother

fast enough that He lost one of His little sandals. What does He see?

His destiny, symbolized by the angels bearing the instruments of His

Passion. The angel to the left, Michael, carries the lance that will

pierce His side, an urn filled with gall, and the reed and sponge which

will carry it to His lips. The angel to the right, Gabriel, bears a

Cross and four nails. His earthly comfort, and ours, is in His mother,

and as He clings to her, she, with her gaze, invites us to do the same.

Icon Styles

Below are

descriptions and pictures of some of the most famous icon types. You

will see the same artistic elements and schemes in icons from different

eras and ritual Churches, in different styles, but with recurring

themes and standardized types.

|

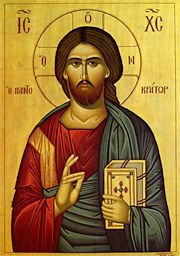

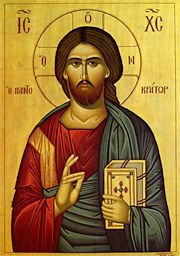

Pantocrator

(Ruler of All, Christ the Teacher)

Christ as

Teacher holding a book, two fingers (raised in a blessing) indicating

His two natures

|

|

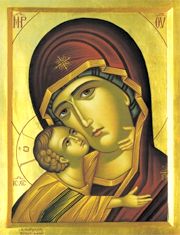

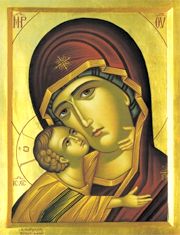

Hodegetria

(Grebenskaya, Our Lady of the Way, The Leader, The Guide of the Church)

Mary holding

Christ and pointing toward Him. The prototype is said to have been

written by St. Luke. (The Polish depiction of Our Lady of Czestochowa,

the famous "Black Madonna," is a variation of the Hodegetria style

icon, as are St. Luke's "Salus Populi Romani" icon kept at St. Mary

Major Basilica , the icon of "Our Lady of Perpetual Help," the "Virgin

of the Three Hands," and "Our Lady of Kazan" ("Kazanskaya") (see below

for some of these in more detail))

|

|

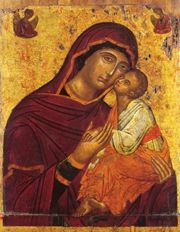

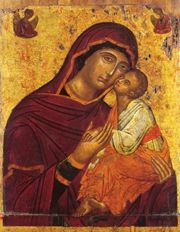

Eleousa

(Elouesa, The Tender Mercy, Virgin of Loving Kindness, Tender Touch,

Sweet Kissing)

Mary holds her

Son, Who touches His face to hers and wraps (at least) one arm around

her neck or shoulder (See La Bruna icon below)

|

|

Glykophilousa

(Oumilenie, Virgin of Tenderness, Who Embraces Gently)

Like the

Eleousa, but the Theotokos embraces Jesus Who caresses her chin

|

|

Panakranta

(Kyriotissa, Queen of Heaven, She Who Reigns in Majesty)

Mary regally

enthroned with Baby Jesus on her lap

|

|

Virgin

Kardiotissa

(Close to the Motherly Heart)

Mary holding

Jesus with their faces touching, His arms are flung wide open around

her neck

|

|

Agiosortissa

(Intercessor)

Mary is shown

alone, in profile, facing toward her left (toward Christ), with hands

held out in supplication

|

|

Virgin

Orans

(the Orante, the Oranta)

Mary is shown

with arms in orante position. A most popular form of this style is the

"Lady of the Sign" (a.k.a. Virgin of the Incarnation, Platytera, or

Panagia), shown at left, in which Mary is shown with arms in orante

position, with Christ enclosed in a circle in her womb. When Christ is

shown in Mary's womb like that, she is known as the "Mother of God of

the Sign," hearkening back to the words of Isaias 7:14, "Therefore the

Lord himself shall give you a sign. Behold a virgin shall conceive, and

bear a son, and his name shall be called Emmanuel." Such icons are

favorites among those who fight abortion.

|

Particular Icons You Should Know

We've already

seen the icon of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, but there are other

particular icons that you should be familiar with:

Salus Populi

Romani

St. Luke is said to have written the famous "Salus Populi Romani"

("Protector of the Roman People") Hodegetria-style icon, shown at

right, which was brought from the Holy Land to Rome by Helena,

Constantine's mother. It is housed in St. Mary

Major Basilica in Rome, a Basilica which was built in response to a

miracle: in A.D.. 358., Our Lady appeared to Pope Liberius and a couple

and told them to build a church at a place she would mark out with snow

on Esquiline Hill. On an August night, she did just that -- a

church-sized, church-shaped area of snow fell on the hill. The people

staked out the area "Our Lady of the Snows" indicated, the Basilica was

built, and Pope Liberius consecrated it. It has been rebuilt over the

years, lastly by Pope Paul V (1605-1621). The Feast of the dedication

of the (original) Basilica is August 5, and in commemoration of the

miraculous snowfall, white rose petals are sprinkled down from the dome

during the Mass that day.

During St. Gregory the Great's pontificate (A.D. 590-604), in the year

A.D. 597, this icon was carried in procession to Hadrian's tomb during

a time of a great plague. Upon arrival at the destination, a choir of

angels was heard singing:

Regina coeli,

laetare, alleluia;

Quia quem meruisti portare, alleluia;

Resurrexit sicut dixit, alleluia.

(Queen of Heaven, rejoice, alleluia;

For He Whom you did merit to bear, alleluia;

Has risen as He said, alleluia.)

To which St.

Gregory replied:

Ora pro nobis

Deum, alleluia.

(Pray for us to God, alleluia.)

Then St. Michael appeared over

the tomb, with sword drawn -- and put his sword back in its sheath as a

sign of the end of the pestilence. This appearance of the Archangel is

the reason why Hadrian's tomb is now known as Castel Sant'Angelo.

In this icon, Mary, dressed in a red tunic and a dark blue mantle with

gold trim, holds Jesus in her left arm. Jesus gazes as His mother as He

holds a book and raises His hand in blessing. Unlike most Hodegetria

type icons, Mary does not point to Christ.

|

|

|

Our Lady With

Three Hands

Another

Hodegetria-style icon you should be familiar with

is the icon known as "Virgin Tricherousa," or "Our Lady With Three

Hands." St. John Damascene (ca. A.D. 676-754/87, Feast Day 27 March), a

great fighter against the iconoclasts, was accused of being an enemy of

the state in which he lived, and as punishment, the Caliph ordered that

one of his hands be chopped off. Afterwards, St. John took the severed

hand, prayed in front of an icon of Our Lady (one said to have been

written by St. Luke), and then fell asleep, waking to find that his

hand was healed. In honor of that healing, he made a hand of silver and

added it to the icon. The altered icon has been duplicated ever since.

You can see the silver third hand in the lower left of the picture.

This icon is at the Serbian Monastery of Chiliandari, Mt. Athos ("Holy

Mountain"), near Ouranoupolis, Greece (in Orthodox hands).

|

|

|

Our Lady of

Czestochowa

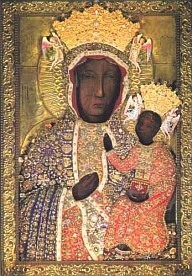

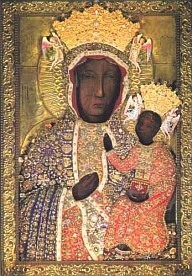

The icon of Our

Lady of Czestochowa -- another icon in the Hodegetria style -- is

another important image, and one with an important and miraculous

History. One of the "Black Madonnas," she can be recognized by her dark

skin tone (partly due to style, partly due to the effects of smoke from

candles), the jeweled clothing, and the slash marks on the cheek (hard

to see in the image at

right, but obvious in person and in good reproductions). This icon is

another said to have been written by St. Luke, and allegedly was

brought from Jerusalem to Constantinople by St. Helena. It ended up in the hands

of the princes of Ruthenia, then was taken to Poland by Prince

Ladislaus, who kept it in the chapel of the Castle of Belz. When the

Saracacens attacked the castle, one of their arrows scarred the throat

of the image. Praying to Our Lady to discover where to place the icon

to keep it protected, Prince Ladislaus had a dream in which he was told

to leave the image on Jasna Gora (Bright Hill) in Czestochowa, where

the icon remains today. He built a monastery and church there and, in

1382, asked Pauline monks to act as guardians of the icon.

In 1430, iconoclast Hussites attacked the monastery and tried to steal

the icon -- but their horses wouldn't budge when they attempted to

carry it away. In a rage, they broke the icon into three pieces and

slashed the cheek of Our Lady's image three times; at the third slash,

the swordsman died! These slash wounds cannot be repaired, though many

had tried over the years.

In 1655, Swedish soldiers, said to have been 12,000 in number, went up

against the monastery but were held off by the 300 religious who had

Our Lady to protect them; in gratitude, King John Casmir declared Mary

Queen of Poland.

In 1920, the Russians gathered in the area to prepare to attack the

Polish people. But the people beseeched Our Lady, and the next day (15

August, the Feast of the Assumption), her image appeared in the skies,

sending the Russians fleeing.

The golden crown that adorns the image today was a gift of St. Pius X

(but Pope Clement XI crowned the image in 1717. Reproductions of the

icon paint in the crown). Many, many miracles are associated with this

icon, and it is quite dear to the Polish people.

|

|

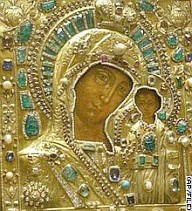

Our Lady of

Kazan

The ultimate origin of the 13th c. Our Lady of Kazan icon (known as

Kazanskaya in Russia) is unknown, but it is said to have been found on

8 July 1579 by a ten-year-old girl, Matryona, who had a dream of the

image resting under ashes in the ruins of one of the Kazan houses.

Legend says that this icon helped the Kazan militia liberate Moscow

from the Polish invasion in 1612.

It was kept in Moscow's Kazan cathedral for a time, but was transferred

to St. Petersburg by Peter the Great. It was stolen during the Russian

Revolution and sold abroad along with other church valuables. The Blue

Army (a Roman Catholic group devoted to Mary) bought it around 1970

from an American collector and presented it to Pope John Paul II in

1993. The Pope, in a move very controversial among traditional

Catholics, returned the icon to Russia in 2004.

|

|

La Bruna

I also have to

mention the "La Bruna" ("The Brown One"), an icon that is of the

Eleousa style but shows Mary with a star with one long tail on her

right shoulder reflecting her purity. Again Our Lady is wearing a red

tunic and blue mantle and veil, which Jesus clings to.

Though it

doesn't show up in this reproduction, Jesus and Mary are surrounded by

large halos, hers with 12 rosettes representing the 12 Tribes and 12

Apostles, His with the Cross. This icon is a 12th c. Carmelite icon,

the original of which is in the Basilica of Carmine Maggiore in Naples,

Italy. |

|

For other important images, some miraculous, see:

Infant of Prague, Santo Bambino di Ara

Coeli, & Maria Bambina on the "Devotion to the Child Jesus" page Infant of Prague, Santo Bambino di Ara

Coeli, & Maria Bambina on the "Devotion to the Child Jesus" page

Our Lady of Good Success in Quito

on the Marian Apparitions page Our Lady of Good Success in Quito

on the Marian Apparitions page

Our Lady of Guadalupe on the Our Lady of

Guadalupe and the Tilma of St. Juan Diego page Our Lady of Guadalupe on the Our Lady of

Guadalupe and the Tilma of St. Juan Diego page

|

|

Infant of Prague, Santo Bambino di Ara Coeli, & Maria Bambina on the "Devotion to the Child Jesus" page

Our Lady of Good Success in Quito on the Marian Apparitions page

Our Lady of Guadalupe on the Our Lady of Guadalupe and the Tilma of St. Juan Diego page