|

Background:

In Greek

mythology, King Minos of Crete defeated King Aegeus of Athens and

threatened to destroy his country unless, every nine years, he

sacrificed seven boys and seven girls to the Minotaur -- a half-man,

half-bull monster -- who lived in the labyrinth in Crete. King Aegeus's

son, Theseus, decided to go to the labyrinth and kill the Minotaur,

releasing the captives and ending the sacrifices once and for all.

On the way to fulfill his mission, he met King Minos's

daughter, Ariadne, who fell in love with him  and

promised to help him find his way back out of the labyrinth if he would

marry her and take her back to Athens with him. She gave him a sword

and a ball of thread and told him to fasten one end of thread at the

labyrinth's entrance and unravel the spool behind him as he walked

through to find the Minotaur and kill him with his sword. Following the

thread in reverse, he'd be able to find his way out of the dark,

twisting passages. Theseus did as Ariadne told him, killed the

Minotaur, and followed the thread back out to safety (neither here nor

there with regard to our purposes, he left Ariadne behind when he went

back to Athens! (The classic-style, seven-circuit, Cretan labyrinth is

shown at right.) and

promised to help him find his way back out of the labyrinth if he would

marry her and take her back to Athens with him. She gave him a sword

and a ball of thread and told him to fasten one end of thread at the

labyrinth's entrance and unravel the spool behind him as he walked

through to find the Minotaur and kill him with his sword. Following the

thread in reverse, he'd be able to find his way out of the dark,

twisting passages. Theseus did as Ariadne told him, killed the

Minotaur, and followed the thread back out to safety (neither here nor

there with regard to our purposes, he left Ariadne behind when he went

back to Athens! (The classic-style, seven-circuit, Cretan labyrinth is

shown at right.)

From 19th c.

archaeologist Rodolfo Lanciani's "Pagan and Christian Rome":

Theseus killing

the Minotaur in the labyrinth of Crete, and labyrinths in general, were

favorite subjects for church pavements, especially among the Gauls. The

custom is very ancient, a labyrinth having been represented in the

church of S. Vitale at Ravenna as early as the sixth century. Those of

the cathedral at Lucca, of S. Michele Maggiore at Pavia, of S. Savino

at Piacenza, of S. Maria in Trastevere at Rome (destroyed in the

restoration of 1867), are of a later date. The image of Theseus is

accompanied by a legend in the "leonine" rhythm: Theseus intravit,

monstrumque biforme necavit ["Theseus entered, and killed the

bi-form monster"].

The classical

world's labyrinths were at first seen by Christians as metaphors for

sin and the powers of Hell, as can be seen from this inscription which

was originally found at the center of the Chartres labyrinth:

This stone

represents the Cretan's Labyrinth. Those who enter cannot leave unless

they be helped, like Theseus, by Ariadne's thread.

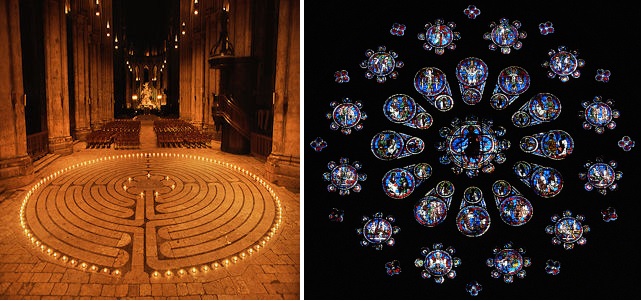

"Ariadne's

thread" -- the help of the woman, Mary, who leads us from the pits of

Hell by pointing toward her Divine Son. Interestingly, the Chartres

labyrinth is situated at the Western end of the nave and has the same

dimensions as the rose window on that side of the cathedral -- a window

which is as high up on the facade as the

labyrinth is away from the West wall. If you could fold the cathedral

over onto itself as if it were hinged where the West facade and floor

meet, the rose window depicting Our Lady would line up perfectly with

-- and cover -- the maze, beautifully symbolizing the power of Mary's

help in our struggle against evil. Stained glass itself has another

level of symbolism, which St. Bernard of Clairvaux described so

beautifully: “As a pure ray enters a glass window and emerges

unspoiled, but has acquired the colour of the glass … the Son of God

Who entered the most chaste womb of the Virgin, emerged pure, but took

on the colour of the Virgin, that is, the nature of a man and a

comeliness of human form, and He clothed himself in it.”

Chartres

labyrinth and West Rose Window Chartres

labyrinth and West Rose Window

Though originally seen as metaphors for the dark powers of Hell and our

need to rely on Our Lady to show us her Son, over time labyrinths came

to be seen quite differently. During the Crusades when Christians

couldn't make visits to the Holy Land, and in the same manner that the Way of the Cross devotion developed as a sort

of substitute "pilgrimage" to the Holy

City, labyrinths came to be used as substitute "Chemins de Jerusalem."

Christians, barred from earthly Zion, would walk the labyrinths, often

on their knees in penance, meditating on the Passion of Our Lord Jesus

Christ.

Sound easy? The

paths of the Chartres labyrinth, for example, make for a journey of 858

feet. Imagine walking on your knees on cold, hard marble for almost the

length of three football fields!

At any rate, the entire symbology of the labyrinth was

reversed: the center of the labyrinth was seen as the goal --

physical Jerusalem or the Heavenly Zion -- instead of that which is to

be escaped -- the pits of Hell. The classical and Carolingian

name "labyrinth" gave way to "Chemin de Jerusalem" or "Rue de

Jerusalem."

No matter which Christian symbology is used to perceive them,

note that, unlike the mythological labyrinth of the Minotaur, church

labyrinths, like classical representations of the Minotaur's

lair, are not designed with dead ends and trickery (for this reason,

some refuse to call them "mazes," though the terms are

interchangeable); they are designed such that one begins at one end and

walks the path, without veering, to the other, the symbol of the

Heavenly Jerusalem (or the escape from Hell). There is only one way in

(or out), one path toward (or away from) the center -- and that path is

direct, as the Way of Christ is direct. Though direct, that path, as in

following Him as "The Way," is a winding road, full of turns and suffering and hardship

(especially if that path is "walked" on one's

knees!). But always, the Heavenly Jerusalem (or the "way out" from sin

and its effects) -- is in sight from any place in the labyrinth, and

one knows that if one remains on that path, he will find himself where

he wants to be.

Be aware that

labyrinths have been enjoying a surge in popularity

recently -- but mostly among pagans and Modernist

Catholics who perceive them as "earth

wombs" or tools for tapping into "earth energies" and such

nonsense. They are over-valued by those who see labyrinths as being magical

and as possessing inherent power -- a

power often imagined as emanating from the earth itself.

In spite of all that, I include the topic here because the traditional

Catholic position must be known, and because I find them lovely

and their original Christian purposes fascinating. Either as

"Chemins de Jerusalem" or metaphors for Hell, the proper use

of labyrinths is quite Catholic and beautiful; it would be sad indeed

if labyrinths were to become associated only with New Agers --

especially when many of the labyrinth designs they use were made

specifically for the great cathedrals and other churches of

Christendom, such as those at Amiens, Reims, and Calais.

Left to Right:

Labyrinths of Amiens, Reims, and Calais

Large, full-sized labyrinths can be walked in penance on one's knees,

walked as "pilgrimage" much the same as the Way

of the Cross, or walked simply as a way of disciplined prayer in

that it forces one to slow down. In all cases, however, Jesus

Christ and the Christian's journey -- not "one's self," "inner

god/ess," "the unconscious mind," etc. -- is always the focus of any

Catholic devotion and prayer!

If you don't have access to medieval labyrinths, facsimiles --

full-sized affairs made of brick, concrete or tiles, or small ones

drawn on paper and traced with a finger -- can

be used. They can be used in the traditional way if size allows, or can

be enjoyed as a

symbol of the Heavenly Jerusalem, the escape from Hell, the Christian

journey, a memorial to the great cathedrals of the Age of Faith -- or

simply admired for their aesthetic beauty, a beauty enhanced by the

knowledge that our Catholic ancestors used these designs for holy

purposes.

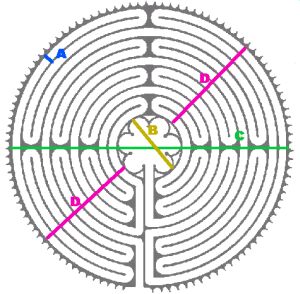

Just for fun: a closer look at the geometry

of the Chartres-style labyrinth or "Chemin de Jerusalem"

The Chartres

labyrinth is an "11 circuit" labyrinth, meaning that from one edge to

the center are 11 "circuits," or rows of paths, made by 12 concentric

circles (i.e, it is 22 circuits across, plus the center). We will let:

A = width of

each circuit (path). This includes the width of the lines that form the

paths (E)

B = diameter of center

C = diameter of entire labyrinth

D = the lenght of only the circuits on both sides of the center, but

not counting the center itself

E = width of actual lines that form the circles and paths

F = radius of center

A = (C-B) / 22

B = C/4

B = 22A / 3

B = C - D

C = 22A + B

C = 4B

C = B + D

D = 3/4C

E = (A/9)2

F = 1/2B

The above equations give the relationships between the size of each

path and the diameters of the center and of the entire labyrinth, and

will let you design your labyrinth by choosing first either the size of

the path, or of the center, or the diameter of the entire thing.

| Example: |

| Say you want

a labyrinth with a diameter (C) of 42 feet. C=42: |

| 1. |

To determine the

diameter of the center (B), divide C by 4:

B = 10.5 feet

|

| 2. |

To determine the

width of the circuits without the center (D), subtract the diameter of

the center from the total diameter C):

D = 31.5 feet

|

| 3. |

To determine the

width of each path (A -- this includes the lines that form the paths!),

divide the number gotten in #2 above by 22:

A = 1.43 feet

|

Example: |

| Say you want

a labyrinth with paths (A) that are each 2 feet wide (the path width

includes the width of the actual lines that form the paths). A=2: |

| 1. |

To determine the

width of just the circuits without the center (D), multiply A by 22:

D = 44

|

| 2. |

To determine the

diameter of the center (B), divide 66 by 3:

B = 14.6

|

| 3. |

To determine the

diameter of the entire labyrinth (C), add D+B:

C = 58.6

|

After you have

your values for A, B, C, D, E, and F, you need to come up with a

measuring guide of some sort. This could be a ruler, if you are drawing

a small design, or a rope if you are making a "life-size" labyrinth in

your garden or some such. Whatever you use as a measuring guide must be

long enough to extend past the edges of the labyrinth from the center

(i.e., it must be a bit longer than 1/2D + 1/2B).

Now, secure the measuring guide to the exact center of B such that the

guide is totally fastened at the center, but can move all the way

around the circle in 360o. Measure out from the center of B,

where the guide is secured, to determine where your

outermost circle will be. To locate that first circle, add the

radius of the center (1/2B ) to 1/2D.

Now you need to mark, in an impermanent way, the entrance and straight

paths that are found on the "south" side of the labyrinth in the

diagram. In churches, the entrances to Chemins de Jerusalem were

built such that when one first entered the labyrinth, one faces

East, as we do at Mass (i.e., in the diagram, the top of the

picture would be "East"). Whatever you decide, from B's

perimeter, lay the guide out so that it reaches the outer perimeter of

the labyrinth, on that side of the labyrinth where you want the

entrance to be. Now measure out two lines, A's width apart, heading

toward the center from the outside of the labyrinth. The actual lines

should be A/9 in width, the width moving from the lines that mark the

first path and toward the center. Now, facing the center, go left

of that path you just made, and mark another line A's width away from

it, making the line no thicker than A/9, the width extending

from that line and toward the other two lines you've already made.

Now you mark the circles of the paths. Mark your guide at regular

distances of A apart (i.e., if A = 2 ft., mark your guide every 2

feet, starting from the perimeter of the center). Lay the guide

down on the surface and mark where its markings indicate. Move

the guide forward a few degrees around the circle, and mark again.

Then connect the dots, taking note of where the turns will be, and

making the lines no more wide than A/9.

Now the turns are added in their proper places, and the rose petals at

the center are added. The rose petals are 6 in number, and their tips

extend halfway from the outer perimeter of the center and the center's

radius.(F/2). There should be a petal point exactly across from the

entrance to the center.

The lunations or little "cogs" on the outside of the labyrinth are

placed as far apart as the diameter of the labyrinth divided by 36

(C/36) (there will be 114 lunations minus one which would have been

where the entrance to the maze is). The length of the lunations will

equal their distance apart. Start the lunations at the entrance: make

the first ones at either side of the entrance exactly 1/2 the distance

away from the entrance path as the lunations are apart from each other:

(C/36)/2.

(To see this graphic by itself for easy printing, click here.

Will open in new browser window.)

|

|